TL;DR: This post explores why linear attention can be seen as a first-order Taylor approximation of the standard Softmax function ($e^x \approx 1+x$). We show that this approximation is only accurate when the attention scores for a given query are tightly clustered around their maximum value. The error of this approximation grows quadratically with the range of the scores, explaining why linear attention often fails to match Softmax performance. We propose that by filtering out low-scoring keys before applying the linear approximation, we can create a hybrid mechanism that constrains the score range, thereby improving accuracy while retaining some efficiency gains.

1.1 Definition of Softmax Attention

Given input embeddings $X \in \mathbb{R}^{N \times d}$, the Query ($Q$), Key ($K$), and Value ($V$) matrices are computed by projecting $X$ with learnable weight matrices $W_q, W_k, W_v$: $$ Q = X W_q, K = X W_k, V = X W_v $$

$$ O_i = \text{Softmax}(\frac{Q_i K^T}{\sqrt{d}}) V = \frac{\sum_{j=1}^N e^{\frac{q_i k_j^T}{\sqrt{d}}} v_j}{\sum_{j=1}^N e^{\frac{q_i k_j^T}{\sqrt{d}}}} = \frac{\sum_{j=1}^N e^{\frac{q_i k_j^T}{\sqrt{d}} - m_i} v_j}{\sum_{j=1}^N e^{\frac{q_i k_j^T}{\sqrt{d}} - m_i}} \text{\quad ,where } m_i = \max_j(\frac{q_i k_j^T}{\sqrt{d}}) $$

1.2 Taylor Expansion of exp(x)

The first-order Taylor expansion of $e^x$ around $x=0$ is: $$ e^x = 1 + x + O(x^2) $$ Applying this to the terms in the Softmax numerator and denominator: $$ e^{\frac{q_i k_j^T}{\sqrt{d}} - m_i} \approx 1 + (\frac{q_i k_j^T}{\sqrt{d}} - m_i) $$ This approximation is the foundation for many linear attention mechanisms, which replace the exponential kernel with a simpler linear dot-product.

1.3 Error Analysis of the First-Order Approximation

Let’s consider the second-order term in the Taylor expansion: $$ e^x = 1 + x + \frac{x^2}{2!} + O(x^3) $$ The error of the first-order approximation ($1+x$) is dominated by the $\frac{x^2}{2}$ term. In the context of attention, $x = \frac{q_i k_j^T}{\sqrt{d}} - m_i$. The accuracy of the linear approximation hinges on the magnitude of this value.

If $|x| = |\frac{q_i k_j^T}{\sqrt{d}} - m_i| < 1$, the higher-order terms of the Taylor series will decrease, and the error is bounded. The approximation holds reasonably well.

However, if $|x| \ge 1$, the higher-order terms can become large, causing the approximation to diverge from the true value of $e^x$. This implies that linear attention is a good approximation only when the dot products between queries and keys are small or tightly clustered around their maximum value.

1.4 Boundedness of the Approximation Term

The validity of the first-order Taylor approximation hinges on $|x| = |\frac{q_i k_j^T}{\sqrt{d}} - m_i|$ being small. Let’s analyze when this condition might hold.

Let $s_{ij} = \frac{q_i k_j^T}{\sqrt{d}}$. Then $x = s_{ij} - m_i$, where $m_i = \max_j(s_{ij})$. By definition, $x \le 0$, so we are concerned with the magnitude $m_i - s_{ij}$. This magnitude is related to the spread of the scores $s_{ij}$, which can be measured by metrics like the $Range$ or the standard deviation.

The approximation error is dominated by the $Range(X) = max(X) - min(X)$

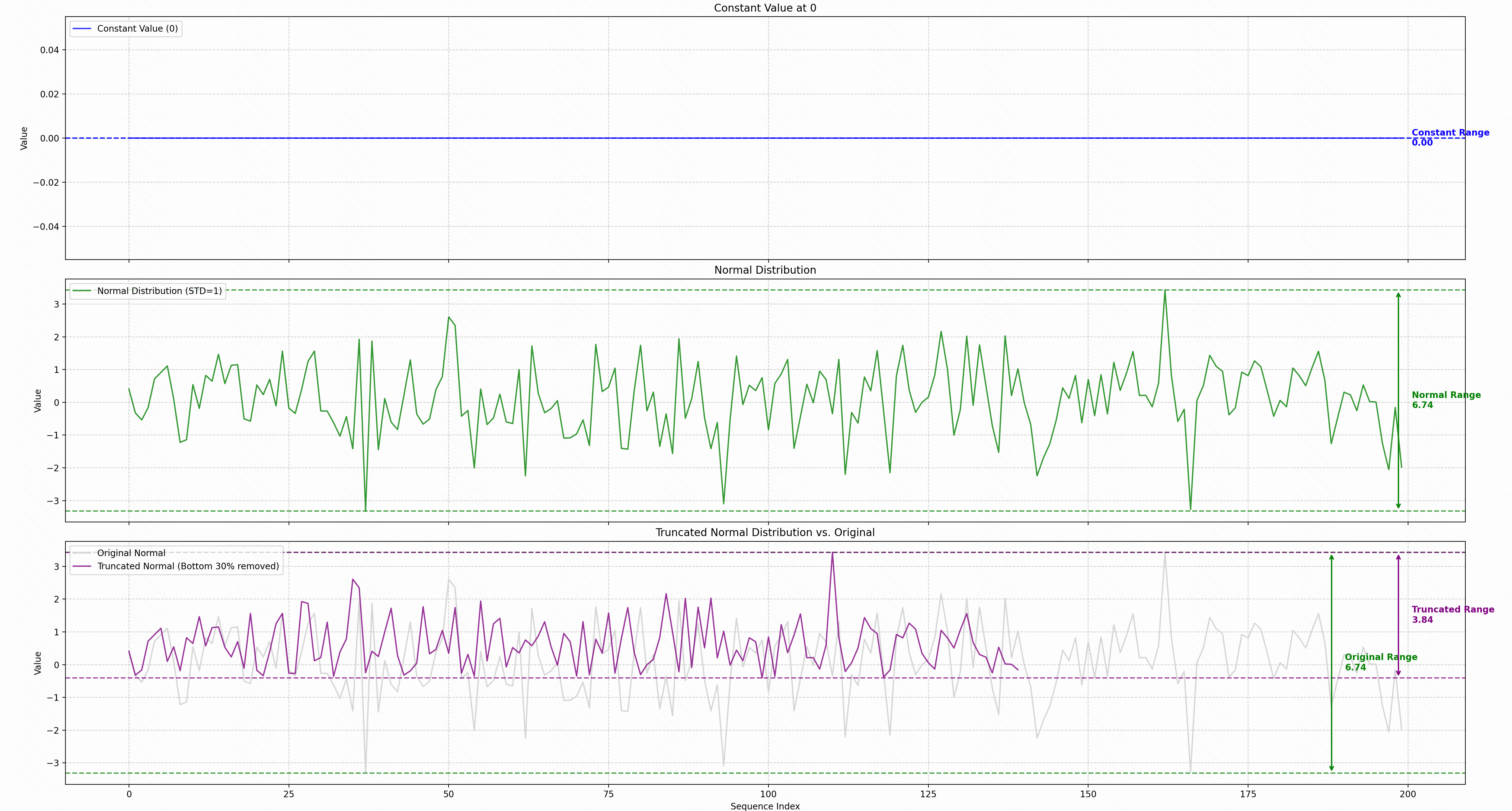

1.4.1 Approximation under a Zero-Range Score Distribution

Let’s consider the ideal case where the scores $s_{ij}$ for a fixed query $i$ are all identical. This can be viewed as a degenerate uniform distribution where the range is zero. $$ s_{ij} = c \quad \forall j $$ In this scenario, the maximum score is simply the constant value itself: $$ m_i = \max_j(s_{ij}) = c $$ The term $x$ used in the Taylor approximation becomes: $$ x = s_{ij} - m_i = c - c = 0 $$ Since $x=0$ for all $j$, the first-order Taylor approximation $e^x \approx 1+x$ is perfectly accurate.

The approximation error, which is dominated by the term $\frac{x^2}{2}$, is zero. This means that when all attention scores are equal, the linear approximation is exact. The Softmax attention mechanism simplifies to an unweighted average of the value vectors.

1.4.2 Approximation under a Unit-Variance Score Distribution

In the Softmax attention, the scaling factor $\frac{1}{\sqrt{d}}$ is chosen to control the variance of the dot products. If we assume the components of $q_i$ and $k_j$ are independent random variables with mean 0 and variance 1 (after normalization), then the dot product $q_i k_j^T$ has a mean of 0 and a variance of $d$. $$ E[\frac{q_i k_j^T}{\sqrt{d}}] = 0 $$ $$ Var(\frac{q_i k_j^T}{\sqrt{d}}) = \frac{1}{d} \sum_{l=1}^d Var(q_{il} k_{jl}) = \frac{1}{d} \sum_{l=1}^d E[q_{il}^2 k_{jl}^2] = \frac{1}{d} \sum_{l=1}^d E[q_{il}^2]E[k_{jl}^2] = \frac{d}{d} = 1 $$ This scaling ensures the scores $s_{ij} = \frac{q_i k_j^T}{\sqrt{d}}$ have a variance of approximately 1.

However, a distribution with unit variance does not imply a small $range$. For instance, if the scores $s_{ij}$ for a fixed $i$ follow a standard normal distribution $\mathcal{N}(0, 1)$, the $range$ of scores is theoretically unbounded. In practice, for a sequence of length $N$, the $range$ can be significantly large.

The approximation error depends on the magnitude of $x = s_{ij} - m_i$. A large $range$ implies that for some $j$, the difference $m_i - s_{ij}$ can be much larger than 1. $$ \text{Range} = \max_j(s_{ij}) - \min_j(s_{ij}) = m_i - \min_j(s_{ij}) $$ If the $range$ is large, $|x| = m_i - s_{ij}$ can be large, causing the Taylor series approximation $e^x \approx 1+x$ to fail. The error term, dominated by $\frac{x^2}{2}$, becomes substantial, and the linear approximation is no longer valid. This explains why linear attention often struggles to match the performance of standard Softmax attention, as the condition for a small approximation error is not guaranteed in practice.

1.4.3 Improving Approximation with Score Filtering

The analysis shows that the linear approximation error is largest for scores $s_{ij}$ that are far from the maximum score $m_i$. This suggests a strategy to improve accuracy: filter out key-value pairs corresponding to low scores before applying the linear approximation. This ensures that the approximation is only used where it is most valid.

Let’s formalize this pre-filtering process. For a given query $q_i$, we first compute the set of all scores $S_i = {s_{ij} \mid j=1, \dots, N}$ and find the maximum score $m_i = \max_j(s_{ij})$.

To ensure the validity of the Taylor approximation $e^x \approx 1+x$, we require $|x| = |s_{ij} - m_i| < \tau$ for some small threshold $\tau$ (e.g., $\tau=1$). Since $s_{ij} \le m_i$, this condition simplifies to $m_i - s_{ij} < \tau$, or $s_{ij} > m_i - \tau$.

We can define a subset of indices $I’_{i}$ that satisfy this condition:

$$ I'_i = \{j \in \{1, \dots, N\} \mid s_{ij} \gt m_i - \tau\} $$

By construction, for all $j \in I’_{i}$, the range of scores is bounded:

$$ \text{Range}' = \max_{j \in I'_i}(s_{ij}) - \min_{j \in I'_i}(s_{ij}) \lt m_i - (m_i - \tau) = \tau $$

With this bounded range, the approximation error for all included terms is controlled. The attention output is then computed by applying the linear approximation only to the key-value pairs indexed by $I’_{i}$:

$$ \text{Attention}(Q, K, V)_i \approx \frac{\sum_{j \in I'_i} (1 + s_{ij} - m_i) v_j}{\sum_{j \in I'_i} (1 + s_{ij} - m_i)} $$

This approach creates a hybrid or sparse attention mechanism. It trades the completeness of considering all keys for a more accurate approximation over a subset of important keys. While this introduces the overhead of a full score computation and filtering step, it can potentially achieve a better balance between efficiency and performance compared to a naive linear attention model.

1.5 Score Space Reduction: An Information-Theoretic View

From an information theory perspective, the effectiveness of linear approximations can be understood by analyzing the size of the score space they operate on.

The unconstrained attention score matrix $S$ is an $N \times N$ matrix where each element is a floating-point number (e.g., FP32). The space of all possible score matrices is immense, with a size of $|\mathcal{R}_{FP32}|^{N^2}$, representing a vast potential for information content (entropy).

For the linear approximation $e^x \approx 1+x$ to be valid, the score matrix $S$ must reside in a low-entropy region where the term $x = s_{ij} - \max_k(s_{ik})$ is small. The standard Softmax and the proposed filtering method can be seen as different strategies to constrain the score matrix to such a well-behaved subspace.

Full Unconstrained Space: The set of all possible $N \times N$ FP32 matrices. This space is too large and unstructured for the linear approximation to be reliable.

Statistically Constrained Space: Standard Softmax attention uses scaling by $\frac{1}{\sqrt{d}}$ to control the dot products. This enforces a statistical constraint, aiming to keep the variance of the scores around 1 ($Var(s_{ij}) \approx 1$). This confines the score matrix to a subspace $\mathcal{R}_{\text{Var} \approx 1}$.

However, as noted, unit variance does not guarantee a small range, so the approximation can still fail. A stronger statistical constraint, such as forcing $Var(s_{ij}) \ll 1$, would create a smaller, more tightly clustered subspace ($\mathcal{R}_{\text{Var} \ll 1}$) where the linear approximation would be more accurate.

- Dynamically Constrained Space: The filtering approach described in Section 1.4.3 enforces a hard, dynamic constraint on the range of scores. For each query, it selects a subset of keys such that the range of their scores is bounded by a small threshold $\tau$. This is equivalent to dynamically projecting the problem into a well-behaved subspace $\mathcal{R}_{\text{Range} < \tau}$ where the approximation error is guaranteed to be small.

In essence, both statistical controls and dynamic filtering are methods to reduce the effective “volume” of the score space. We trade the full expressive power of the Softmax function—the ability to model highly sparse, high-entropy distributions—for computational efficiency by operating within a restricted subspace where a simple linear function is a sufficiently good approximation of the exponential kernel.

Reference

- Lei, J., Zhang, D. and Poria, S. (2025) “Error-Free Linear Attention is a Free Lunch: Exact Solution from Continuous-Time Dynamics.” arXiv. Available at: https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2512.12602.